Great White Shark (Carcharodon Carcharias)

Share

When it comes to ocean legends, the great white shark is the undeniable rock star of the deep. Known scientifically as Carcharodon carcharias, these apex predators have inspired fear and fascination for centuries, from the iconic "Jaws" theme that made beachgoers wary to their frequent appearances in blockbuster documentaries like "Shark Week." Great whites can grow over 20 feet long, weigh more than a small car, and boast a bite force strong enough to crush bones like potato chips. But behind their terrifying reputation lies a surprisingly nuanced creature, vital to marine ecosystems and more misunderstood than menacing. So, grab your snorkel, and let's dive into the fascinating world of these toothy titans!

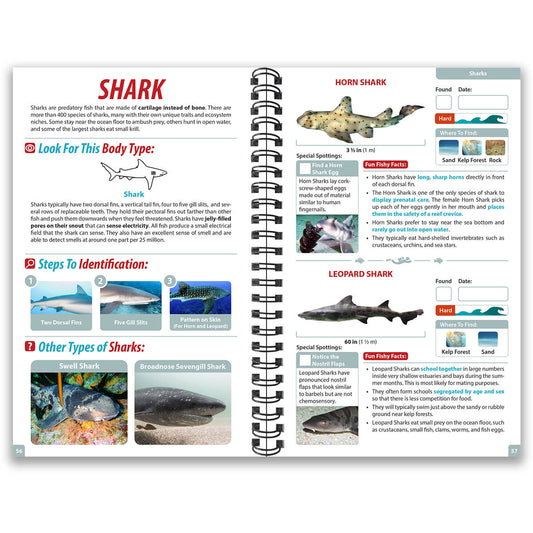

How to Identify the Great White Shark:

- Countershading: The Great White Shark exhibits a unique coloration pattern with a dark upper body—ranging from blue, gray, to brown—and a stark white underside. This countershading assists in camouflage within the ocean.

- Body Shape: Characterized by a robust, torpedo-shaped body, the Great White features a blunt, conical snout, giving it a distinctive profile compared to other large sharks.

- Fins: It possesses large pectoral and dorsal fins, alongside a prominent crescent-shaped tail. These fin structures are more robust than those found in similar species.

- Teeth: Equipped with large, triangular, and serrated teeth, the shark's jaws are built for efficiently cutting through flesh and breaking bone.

- Size: Adults typically range from 4 to 6 meters (13 to 20 feet) in length, while females are generally larger than males. This size distinguishes them from smaller predatory species, such as porbeagles.

- Skin Texture: The skin of the Great White is covered in dermal denticles, providing a rough texture akin to sandpaper. This adaptation serves as protection and contributes to improved hydrodynamics.

Commonly Confused with:

The Great White Shark is often mistaken for several other shark species due to similarities in size, shape, and coloration. Here are the species most commonly confused with the Great White Shark:

- Mako Sharks: Mako sharks, specifically the shortfin mako, can look similar to Great Whites because of their streamlined body shape and sharp, triangular teeth. However, Mako sharks are generally slimmer, possess a more pointed snout, and have a darker coloration on the top with a distinctive metallic sheen that sets them apart from Great Whites.

- Salmon Sharks: Found in the North Pacific, salmon sharks share a similar stocky build and coloration with Great Whites. Nevertheless, they are usually smaller in size and exhibit shorter, more rounded snouts. Additionally, their diet primarily consists of salmon, which is a crucial aspect of their name.

- Porbeagle Sharks: Another relative of the Great White, porbeagle sharks share a similar shape and coloration but are significantly smaller, typically measuring only about 6-8 feet compared to the Great White’s potential length of 20 feet. Their robust build and the presence of serrated teeth can sometimes lead to confusion, but their size is a clear distinguishing factor.

These differences in size, shape, and coloration are key to identifying these species, helping to reduce confusion with the iconic Great White Shark.

Great White Shark Quick Facts

Scientific Name: Carcharodon carcharias

Size: Up to 20 feet (6.1 meters)

Weight: Over 4,000 pounds (1,814 kg)

Region: Found worldwide in temperate and subtropical waters

Endangered Status: Vulnerable

The Diet of Great White Sharks

The Great White Shark is a fascinating apex predator known for its diverse and adaptable diet, which plays a crucial role in its survival and ecological balance.

Primary Prey

Adult Great White Sharks primarily hunt marine mammals, making them essential players in the oceanic food web. Their preferred prey includes:

- Seals: Such as grey seals, northern elephant seals, and harbour seals.

- Sea lions

- Dolphins: Including harbour, dusky, and bottlenose dolphins.

- Small whales: Occasionally, they will target species like beaked whales and humpbacks.

Other Prey

In addition to marine mammals, Great Whites have a varied diet that includes:

- Fish: Tuna, mackerel, and salmon are common targets.

- Seabirds: Gulls, penguins, and cormorants can be opportunistic meals.

- Rays and Turtles

- Other Sharks: They are known to cannibalize smaller shark species.

- Carrion: The remains of dead whales or large marine creatures also serve as a food source.

Hunting Techniques

Great White Sharks are opportunistic hunters that often employ ambush tactics. They are known for their ability to:

- Breach: Launching themselves from the water to catch prey off guard.

- Stalk: Gradually approaching their target before lunging forward to attack.

Dietary Variations

Their diet is not static; it varies based on:

- Age: Young sharks primarily eat smaller prey like squid and stingrays, while adults seek more calorically dense marine mammals.

- Location: Specific regions, such as South Africa and California, can shape their dietary choices based on local prey availability.

Differences Between Male and Female Great White Sharks

In examining the Great White Shark, key distinctions can be seen between males and females, showcasing sexual dimorphism, where the two sexes exhibit different physical characteristics.

Size

- Females are generally larger than males. They can grow up to 20 feet (6 meters) in length, while males typically reach a maximum of approximately 15 to 17 feet (4.5 to 5.2 meters).

Growth Patterns

- Females tend to grow slower than males, mainly due to their different feeding patterns. The larger prey they focus on helps support their reproductive needs, significantly influencing growth rates.

Behavioral Patterns

- Males often display more aggressive and territorial behaviors, especially during mating season, engaging in activities like biting and tail-slapping to assert dominance. In contrast, females are generally more passive, sometimes entering a state of tonic immobility to evade male advances.

Migration and Social Behavior

- Females often migrate to specific areas to give birth, showing a preference for certain nurseries. Males, however, tend to be more migratory in their search for food and mates, while females may become solitary during pregnancy or while raising young.

Physical Characteristics

- Females possess thicker skin than males, which results from the biting behavior males exhibit during mating. This difference is a fascinating aspect of their sexual dimorphism.

Reproduction of Great White Sharks

The Great White Shark exhibits unique reproductive strategies that highlight the complexity of their life cycle.

Reproductive Mode

- This species of shark is ovoviviparous, meaning that fertilized eggs hatch inside the mother's body, leading to the birth of live young.

Sexual Maturity

- Males reach sexual maturity at around 10 years of age and approximately 11.5 to 13 feet (3.5 to 4 meters) in length. Females take longer, maturing between 12 to 18 years and measuring about 15 to 16 feet (4.5 to 5 meters).

Gestation and Litter Size

- The gestation period is typically around 12 months, but it can range from 11 to 18 months. Litters generally consist of 2 to 10 pups, with larger litters of up to 14 to 17 pups occurring in some cases.

Intrauterine Development

- Inside the womb, embryos undergo oophagy, feeding on unfertilized eggs, and engage in embryophagy, a form of cannibalism where more developed embryos consume their less-developed siblings. This behavior enhances survival odds for the strongest pups.

Birth and Independence

- At birth, pups measure about 3 to 5 feet (1 to 1.5 meters) and are completely independent, receiving no parental care. Females typically breed every two years, allowing time to recover physically and energetically for another pregnancy.

Migration of Great White Sharks

Great White Sharks are remarkable migratory animals, covering vast distances as they move between essential habitats. This migration is critical for their survival, aiding in hunting and reproduction.

Migration Patterns

Great White Sharks undertake extensive migrations, often exceeding 2,500 miles annually. Their patterns include:

- Foraging and Reproductive Areas: These sharks migrate between feeding grounds, usually rich in prey like seals, and areas suitable for reproduction.

- Seasonal Movement: In the western North Atlantic, they migrate predictably from Newfoundland to the eastern Gulf of Mexico, spending summers in cooler waters off New England and winters in warmer southern regions.

- Pacific Migration: In the Pacific, these sharks journey from California’s coastal waters to the "White Shark Cafe"—a deep-water area between California and Hawaii—before returning to their feeding grounds in late summer.

Energy Storage and Navigation

Before long migrations, Great White Sharks store energy in their livers through fat. This energy is crucial for their lengthy travels, influencing their buoyancy—how easily they float in water.

Additionally, these sharks exhibit site fidelity, consistently returning to familiar locations year after year. This behavior suggests they possess sophisticated navigational abilities, likely guided by environmental cues such as water temperature and current patterns.

Seasonal Influences

Their migrations are also affected by temperature preferences, typically favoring waters ranging from 50 to 80°F (10 to 27°C). Notably, gestating females may migrate to deeper waters, avoiding the attention of competitive males during this sensitive period.

Ultimately, the migratory behavior of Great White Sharks reflects their adaptability and plays a crucial role in their life history.

Habitat of Great White Shark

Great White Sharks are remarkable creatures that roam a vast range of marine environments. Their habitats span from coastal areas to deeper offshore waters across the globe.

Geographic Distribution

These sharks can be found in almost all coastal and offshore waters between 60°N and 60°S latitudes. Key regions include:

- United States: Notably California and the Northeast

- South Africa

- Japan

- Oceania

- Chile

- Mediterranean Sea

Water Temperature

Great White Sharks thrive in waters that typically range from 12 to 24 °C (54 to 75 °F). While they generally prefer these temperatures, they are capable of tolerating slightly colder or warmer waters.

Habitat Preferences

Their habitat choices are often determined by the availability of prey, as they are known to frequent areas rich in marine mammals. They typically inhabit:

- Coastal areas and continental shelves

- Bays and surf zones when searching for food

- Juvenile habitats in shallow coastal nurseries

Adult Great Whites favor offshore environments, while young sharks tend to remain in shallower waters during their early lives.

Depth Range

Great White Sharks can be found at various depths, from the surface to depths of up to 1,200 meters (3,900 feet). They usually inhabit regions between the coastline and deeper waters, showcasing their versatility in adapting to different marine environments.

The Role of Great White Sharks in the Ecosystem

Great White Sharks play an essential role in maintaining the natural balance of marine ecosystems. Their presence and activities significantly influence the health and diversity of the ocean.

Apex Predators

As apex predators, Great White Sharks occupy the top of the food chain, regulating the populations of prey species. This includes animals like seals and sea lions. By keeping these populations in check, they prevent overpopulation, which could otherwise lead to disruption in the ecosystem and a decline in biodiversity.

Trophic Cascades

The effects of Great White Sharks extend beyond direct predation, triggering trophic cascades. A trophic cascade is a series of changes in the population and behavior of species in a food web resulting from the removal or addition of a top predator. Their hunting helps manage not only prey species but also influences the distribution and behavior of those prey, enhancing the overall health of marine environments.

Ecology of Fear

This influence is often referred to as the "ecology of fear," where the presence of these sharks alters the behavior of prey species, promoting grazing activities that support vital habitats like seagrass beds and coral reefs.

Indicators of Ocean Health

Great White Sharks are also indicators of ocean health. As top-level consumers, changes in their populations can reflect broader environmental shifts, such as pollution and habitat degradation. Their presence is a sign of a balanced ecosystem, while declines may indicate ecological stress.

Overall, the role of Great White Sharks is critical in preserving the structure and function of marine ecosystems, ensuring their resilience and diversity.

Unique Adaptations of the Great White Shark

The Great White Shark boasts a range of unique adaptations that enhance its effectiveness as a predator and enable it to thrive in diverse marine environments.

Body Shape and Swimming Efficiency

- The torpedo-shaped body enables incredible speeds, reaching up to 35 miles per hour (about 50 kilometers per hour).

- A symmetrical tail and paired dorsal and pectoral fins contribute to its swimming efficiency, allowing for agile movements through the water.

Thermoregulation

- These sharks exhibit a remarkable adaptation known as regional endothermy, allowing certain parts of their bodies to remain warmer than the surrounding water. This warmth aids in maintaining high speeds while hunting.

Sensory Innovations

- Equipped with electroreceptors called the ampullae of Lorenzini, Great White Sharks can detect electric fields produced by prey, enhancing their hunting capabilities.

- Their skin is covered in dermal denticles, which serve two purposes: they reduce drag as the shark swims and protect it from abrasions.

Camouflage

- Great Whites use a form of countershading with a dark grey back and white belly. This coloration helps them blend in with light from above while avoiding detection from below, making it harder for prey to see them as they approach.

Feeding Mechanisms

- Their formidable jaws house large, triangular, serrated teeth that are perfectly adapted for slicing through the blubber of marine mammals, making their feeding more efficient and effective.

These adaptations highlight the evolutionary prowess of the Great White Shark, positioning it as one of the ocean’s most efficient predators.

Symbiotic Relationships of the Great White Shark

The Great White Shark engages in fascinating symbiotic relationships with various marine species, showcasing the interconnectedness of ocean life. These interactions can be categorized into three main types: mutualism, commensalism, and parasitism.

Mutualism: A Cooperative Connection

In a mutualistic relationship, both species benefit. Great White Sharks frequently interact with cleaner fish, particularly at designated cleaning stations. Here’s how it works:

- Benefit to the Shark: The cleaner fish remove ectoparasites (small organisms that live on the surface) from the shark’s skin, promoting its health.

- Benefit to the Cleaner Fish: These fish gain a vital food source by consuming the parasites.

Commensalism: A One-Sided Benefit

The Great White Shark also maintains a commensalistic relationship with remora fish. In this scenario:

- For the Remoras: These fish attach themselves to the shark, feeding on leftovers and parasites without harming the shark.

- For the Shark: The remoras’ presence is generally neutral; the shark is unaffected by them.

Parasitism: A Harmful Interaction

In contrast, parasitism represents a relationship where one species benefits at the expense of another. Great White Sharks can host certain parasites, such as copepods. These tiny creatures attach themselves to the shark’s cornea and feed on its tissue, potentially affecting the shark’s vision.

Understanding these symbiotic relationships deepens our appreciation for the ecological balance found in marine environments, illustrating how interconnected life in the ocean truly is.

Life Cycle of the Great White Shark

The life cycle of the Great White Shark is a complex journey that unfolds through several critical stages, demonstrating their adaptability and resilience in the marine environment.

Early Life

Newborn pups face immense challenges; many do not survive their first year due to threats from predators and the need to hunt on their own. This vulnerability makes their early life critical for their survival.

Growth Stages

The growth of a Great White Shark occurs in several distinct stages:

- Pups: Newly born sharks that are highly vulnerable.

- Young of the Year: Sharks in their first year.

- Juveniles: Sharks transitioning to more independence.

- Subadults: Growing sharks that are not yet mature.

- Adults: Fully grown individuals that reach significant sizes.

Maturity Milestones

- Males reach sexual maturity around 26 years and lengths of 3.4 to 4.0 meters (11 to 13 feet).

- Females take longer, maturing at about 33 years and lengths of 4.6 to 4.9 meters (15 to 16 feet).

Adult Life

Great White Sharks thrive as apex predators, living for up to 70 years in some cases. This remarkable lifespan underscores their intricate life cycle, allowing them to navigate the ocean's complexities over decades.

Conservation Efforts for the Great White Shark

Conservation of the Great White Shark involves a blend of protective legislation, scientific research, public education, and habitat preservation.

Regulatory Protections

Great White Sharks benefit from various federal laws and international agreements aimed at preventing extinction. In the United States, they are protected under:

- The Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation Act

- CITES Appendix II, regulating their trade globally

California has extended protections since 1994, forbidding any pursuit, capture, or possession of these majestic creatures.

Research and Monitoring

Organizations like the Atlantic White Shark Conservancy conduct critical research, utilizing tagging and tracking technologies. They deploy acoustic receivers and buoys to monitor shark movements, which helps scientists understand:

- Behavioral patterns

- Habitat preferences

- Population dynamics

This vital information informs effective conservation strategies.

Public Safety and Education

Public safety initiatives focus on educating communities about the behavior of Great White Sharks. Efforts include:

- Collaborating with local authorities on data-driven public safety measures

- Promoting understanding to dispel myths about shark behavior

Through education, organizations improve safety while fostering appreciation for marine life.

Advocacy and Habitat Protection

Organizations like Sea Shepherd actively engage in patrols in shark habitats, working to prevent illegal activities like fishing and shark finning. Advocacy efforts emphasize the ecological importance of Great White Sharks, reinforcing their role in healthy marine ecosystems.

Strategies for habitat protection include:

- Establishing Marine Protected Areas to safeguard critical breeding and nursery habitats

These conservation efforts collectively combat threats such as overfishing, habitat degradation, and pollution, highlighting the need for ongoing protection of these incredible apex predators.